In approaching a large collection of puzzles and rebuses such as those of the Reading Rebus project, it’s natural to wonder why the form exists and how it has permeated so many parts of the world’s imagination.

What is a rebus?

There are many definitions of the term rebus, which is from the latin phrase for “by things” (M-W Online) and in many cases has been attributed to the phrase “non verbis, sed rebus” (not by words, but by things) (Wikipedia, first citation). A rebus is most commonly known to be a puzzle where a message is encoded in some way by pictures replacing words in part or as a whole.

However there are other forms of rebus which rely on a graphical play of the words or word order (an example can be found in #10 of the Gazette de Rebus puzzle); or in some cases, words symbolizing other words in a complex riddle for a call-and-response (as with this example by Phillis Wheatley Peters.)

In his review of Rébus de la Renaissance, Henri Weber breaks down the symbolic rebuses into the following categories:

- analytical rebus: an image corresponds in a 1:1 relationship to a phoneme, syllable, or complete word, as with 🐝 and “bee.”

- synthetic rebus: where the solver interprets an association from the image and ascribes a phoneme or complete word to that image, as with 🐝 🐝 and “Beyoncé hive (fans).”

- mixed rebus: has a bit of both.

For text-based rebuses a similar bit of logic is useful, but we would add two distinctions:

- Text rebuses which use text visually to create a new text solution as in

LE

VEL

- Text rebuses that symbolically use text to encourage solvers to associate words into a new text solution (Wheatley Peters, Voltaire).

Some rebuses are independent of phonemes and language entirely, and like modern emoji conversation work with the pure representation of the thing itself without knowing the parent language. Anthropologist and folklorist Michael J. Preston calls such images “Droodles,” a logograph that can communicate over several languages, as with 🦆 to indicate “duck.” These images are often used in children’s rebuses, language-learning rebus puzzles, and in some casual correspondence in this collection (and in the example here, a way that emojis can be used).

Symbolism

Rebus forms have also been metaphorically centered and evocative, standing on their own as art pieces without knowledge of their underlying riddle. For example, in art from the Song period in China, it was common to “read” a painting by its elements, as with this example from the Met:

![This painting is a rebus or pictorial pun, that conveys a wish for success on an examination. The Chinese title of the painting, Yuan lu ("gibbons and deer"), is a homophone for the expression "First [place gains] power." Thus, the painting must be read as a text, its images read as words.](https://readingrebus.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/DP153510-1024x837.jpg)

In it, the gibbons and deer would form a bit of wordplay, as these elements would sound like the phrase “first place gains power.” Similar motifs are found in other pieces that have rebus elements but are also meant to be viewed without the necessity of “solving,” as in some heraldry, signet rings, and ancient Greek coins (Danesi, 60).

How old are rebuses?

No one can truly say! According to some, the rebus form can be found as far back as ancient Greece, where rebus coins were used as currency (Danesi, 60).

In our collection we were able to find rebus paintings from the 1200s as well as heraldry from the 1500s that boast rebus imagery and symbolism.

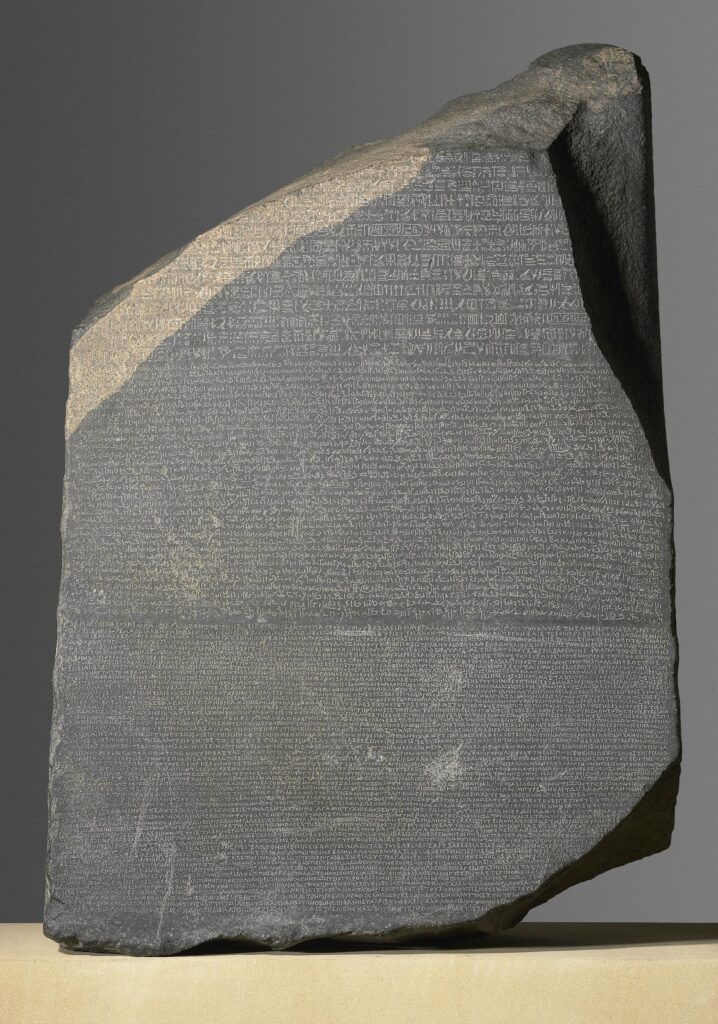

The rise of the rebus form in Europe may have been bolstered by the rediscovery of the Rosetta Stone after France’s invasion of Egypt in 1799 (and its great translation efforts through the beginning of the 19th century, British Museum Blog, Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Rosetta Stone), and as such many rebuses from this era are often termed “hieroglyphic” in nature. This trend of the rebus rising appears about 200 years after the noted use of the rebus by the families of Picardy (now in Haut-de-France in the northeast) for their heraldic images on paper pamphlets. These pamphlets were used at the time for religious celebrations where not all participants would be able to read written words. (Danesi, 60) It is possible that the logographs of the Picardy pamphlets yielded a model in Europe that the Rosetta Stone translation fascination continued to aid.

Why do we make things into puzzles anyway?

For those of us who love puzzles, this question has an easy answer: they’re fun! However for many, our love of puzzles is simply confounding. For example, in our puzzling and hypercommunicative era, it is possible to be overwhelmed by rebuses. Why do we continue to make word puzzles and games when we could just send a message? After the invention of the telegram, the telephone, the email, the tweet, and even the rebus-esque emoji — why do we continue to make things puzzling? Or, to be as clear as can be: isn’t life hard enough?

Like many puzzles, there are no easy answers. However some theories have better answers than others. Here’s one I like for our fraught era especially, which is interpreted and remixed from Danesi:

The puzzle represents a light power play interaction between puzzle maker and solver. The puzzle maker has power in that they know the solution and have constructed an elaborate path to get to the solution. The solver enjoys solving a puzzle like a rebus or riddle because it challenges the power dynamic and when solved, upends it entirely. The catharsis that the solver experiences as a result of solving a puzzle is linked to this triumph over the problem.

In the case of rebuses which have often been used as romantic correspondence and also as political satire, this adds a new dimension! Rebuses in many cases have an element of the classical riddle like that of the Sphinx, as it implies that greater overall knowledge is behind the images if only the solver can make it through the challenge. Therefore it is reasonable that so many of our found rebuses’ solutions are parables or other cultural truths.

It is true however that puzzles are fun, especially rebus puzzles due to their verbal and visual play. Those in the modern era who has used a 🌊 emoji to signify a “wave hello” have started their foray into rebus.

Bai, Qianshen. Image as Word, A Study of Rebus Play in Song Painting (960-1279). 1999, pp. 57–72.

Clinchy, Evans. “Saturday, April 10, 2021 Daily Crossword Puzzle – The New York Times.” The New York Times Games, 10 Apr. 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/crosswords/game/daily/2021/04/10.

Danesi, Marcel. The Puzzle Instinct: The Meaning of Puzzles in Human Life. Indiana University Press, 2002.

Definition of REBUS. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/rebus. Accessed 2 May 2021.

“Everything You Ever Wanted to Know about the Rosetta Stone – British Museum Blog.” British Museum Blog – Explore Stories from the Museum, https://blog.britishmuseum.org/everything-you-ever-wanted-to-know-about-the-rosetta-stone/. Accessed 2 May 2021.

“French Campaign in Egypt and Syria.” Wikipedia, 14 Mar. 2021. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=French_campaign_in_Egypt_and_Syria&oldid=1012018631.

Huizinga, Johan. Homo Ludens a Study of the Play-Element in Culture. Angelico Press, 2016. “Picardy | History, Culture, Geography, & Map.” Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/place/Picardy. Accessed 2 May 2021