18th– and 19th-century Britain and America popularized the genre of verbal rebuses: “poem[s] that provide clues to letters or syllables that spell out words” (Lewis 178) or describe a series of images whose correct names form an acrostic that solves the poem’s riddle. Originating in English periodicals, these “acrostic rebuses” regularly appeared in newspapers and gazetteers across the North American settler colonies and the British Transatlantic, including the Caribbean. The “Rebus” would be published in one issue and its “Answer” in the next, much as the New York Times publishes its crosswords (of which these rebuses are a forerunner) over a pair of weeks.

Phillis Wheatley Peters’ foundational collection, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, produced in Boston but published in London in 1773, ends with just such an Acrostic “Rebus” and its “Answer.” While her work proves ever more fundamental to American literature and culture, this pair remains largely understudied, especially in the context of historical rebuses. By placing these poems alongside Acrostic Rebuses published in British settler and chattel-slavery colonies in the same years, readers can further recognize the extent of Wheatley Peters’ self-authorization and political engagement. 1

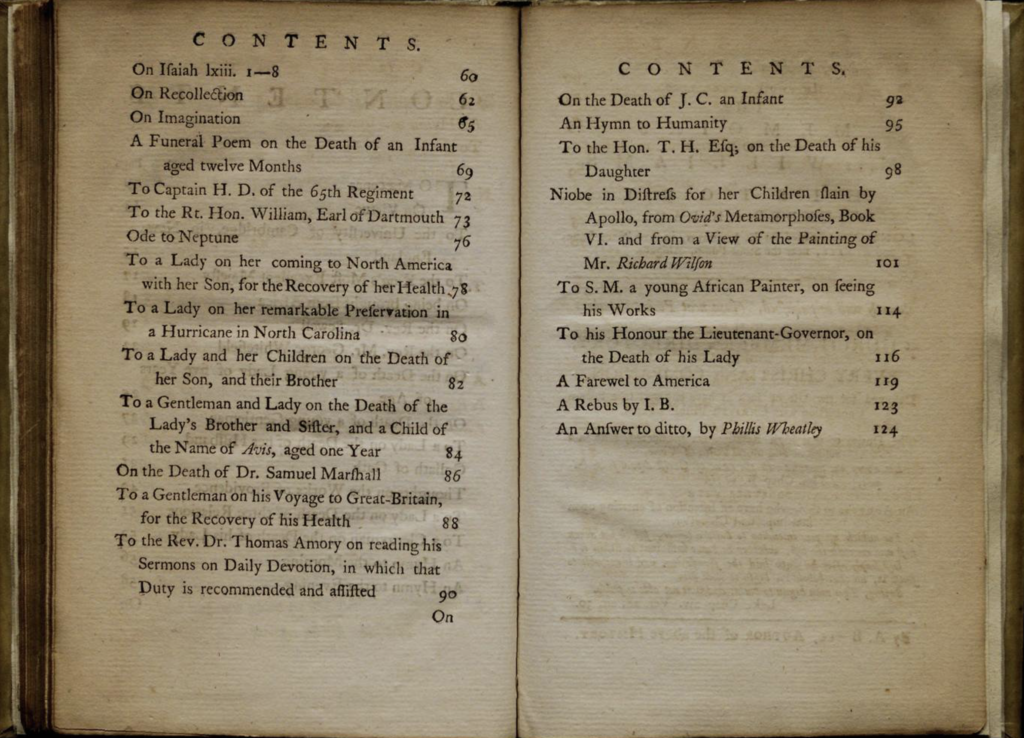

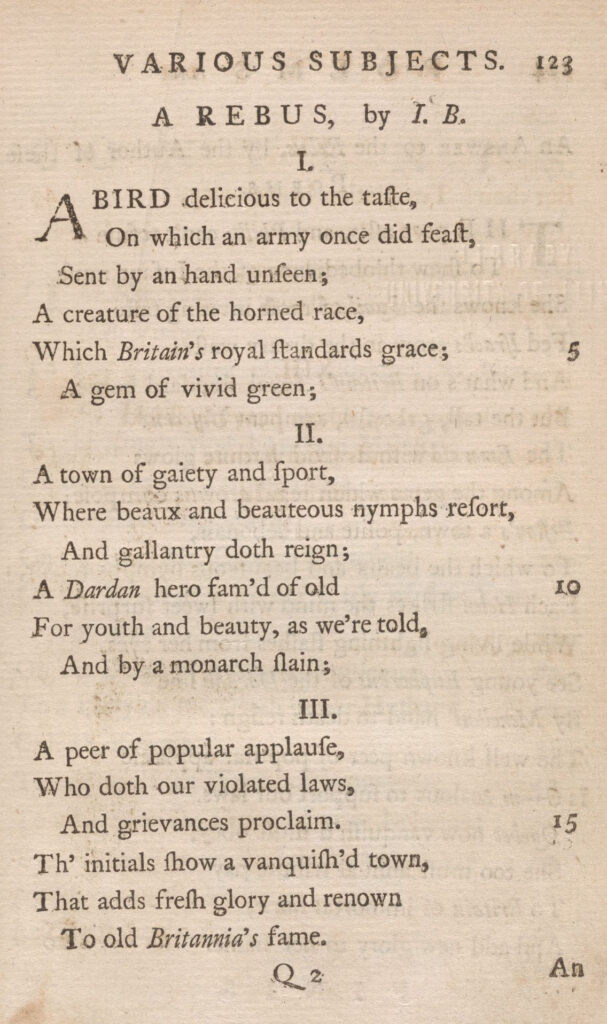

Like the many verbal rebuses from the period that appear under pseudonyms or the writer’s initials only, “A Rebus” is attributed simply to “I.B.” in Poems on Various Subjects: both in its title on page 123 verso and in the Index to the edition. Despite the disguise, most scholars identify “I. B.” as the (future Massachusetts Governor and College Founder) James Bowdoin listed in the opening letter of “Attestation” or authentication “To the PUBLICK,” of the volume. 2

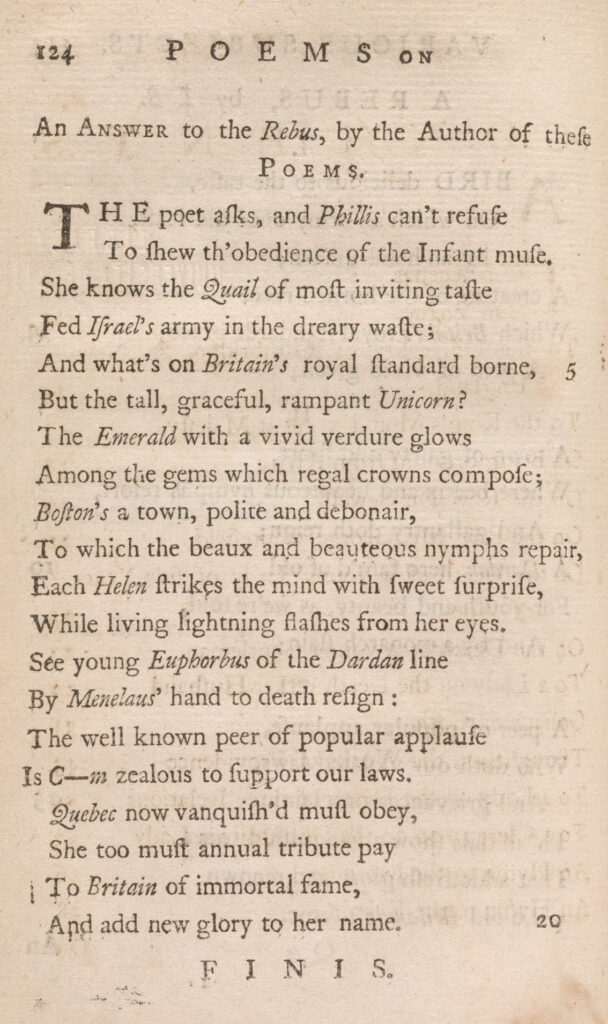

In contrast, the title of “An Answer to the Rebus,” the concluding poem in the volume, emphasizes its creation “by the Author of these POEMS” on the following page, 124 recto. The text’s actual final line, at the bottom of the Index, goes even further: it presents the closing poem’s title as “An Answer to ditto, by Phillis Wheatley 124” and thus stresses the specific name of “the Author” as literally the last words in her book. 3

By evoking and truncating this earlier mention of I[ames] B[owdoin], while simultaneously amplifying her own name and authority, Wheatley Peters establishes a powerfully different persona for herself at the work’s end than one finds at its start. Pace critics who see the pair as “not fit[ting] the spirit of the volume” (Shields 2004), Katherine Clay Bassard suggests the stakes in Wheatley Peters’ choice to conclude with these particular poems:

This inclusion is neither frivolous nor gratuitous but represents Wheatley’s own answer to the letter of attestation (or, indeed to the question such a letter raises—did she know what she was doing?). In ‘An Answer to the Rebus,’ Wheatley actually solves the versified riddle of one of the authenticators. In a gesture of self-Authentication, Wheatley responds to the issue of epistemology by demonstrating that she can, indeed, crack the codes of Western discourse. And her decoding encodes the point of entry for an African Americanist theorizing. (Spiritual Interrogations 1999)

Making use of a genre that ritualizes the act of deciphering as a public exchange, the Answer to the Rebus displays Wheatley Peters’ extensive Biblical, Classical, and local diplomatic expertise in a re-enactment and subversion of the book’s opening scene. By juxtaposing her own skillful application of cultural capital with that of “the best Judges,” Wheatley Peters fashions her retort as a comprehensive, attenuated “Answer to ditto”—Phillis Wheatley’s reply to the Boston authorities’ parade of social power and European knowledge. In doing so she labels the rebus, or its author I.B., as so thoroughly iterative as to merit only the mark of utter sameness.

Even without the reminder of its generic predictability, late-18th-century readers would recognize Wheatley Peters’ inclusion of an acrostic rebus as signaling her participation in an arena central to alternative modes of authorship and citizenship in the British colonies, a zone distinct from the other spaces within which the volume places her (as dedicatory “servant” to patron Selena Hastings, Countess of Huntington, or as a solitary writer at her desk, for example).

Wheatley Peters published poems, primarily odes and elegies, in newspapers and periodicals beginning in 1767, but the acrostic rebus invited a different relationship between writer and audience. Paul Lewis argues that the Acrostic Rebus served as a unifying genre in Colonial Boston, where literally disenfranchised inhabitants, particularly women and the property-less, could constitute themselves in some way as “citizens” by “participat[ing] in the give-and-take of Boston’s nascent literary culture” (Lewis 4). Lewis claims that when “played by citizen poets and their fans who could become citizen poets themselves by submitting solutions,” and when distributed widely in periodical form, “these short verse exercises [could] be enjoyed as modest invitations to join an interactive, literary community” (Lewis 179). Admission to an imagined literary polis would be “modest” compensation indeed for an enslaved woman, compared to the civic status conferred by emancipation, land ownership, and suffrage. Yet Acrostic Rebuses from newspapers in the years contemporaneous to Whitney Peters’ Poems also reveal a more disruptive dimension to the genre than Lewis acknowledges, a duality that Whitney Peters’ work appropriates and develops further.

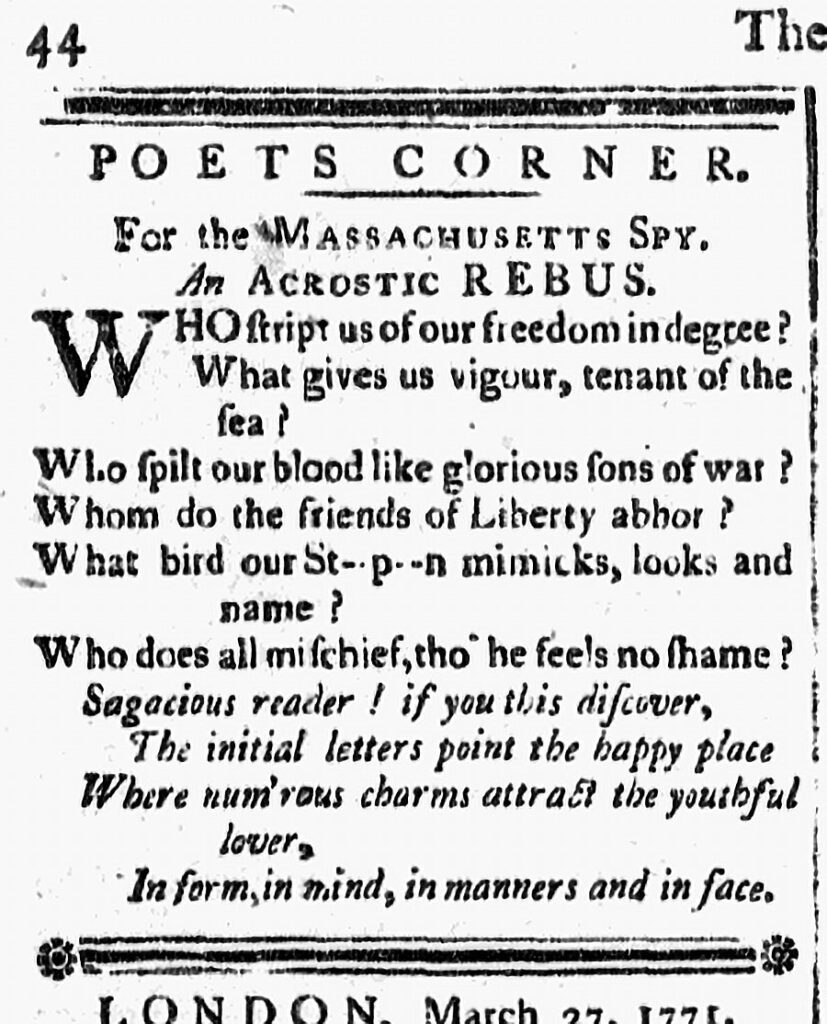

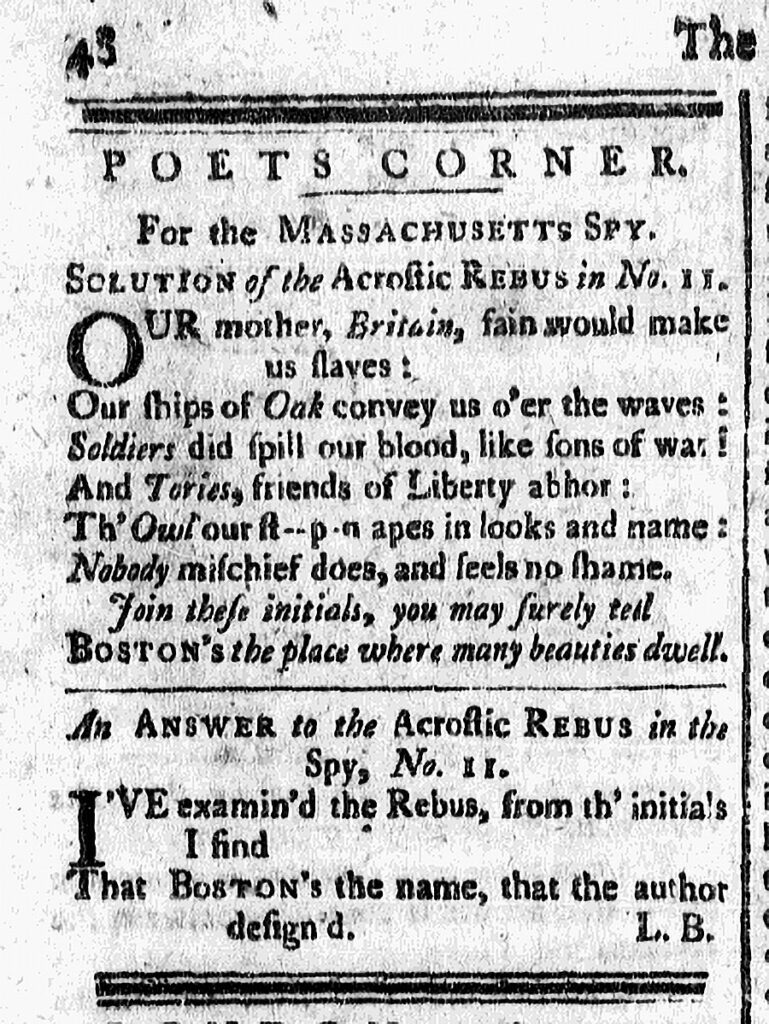

For example, the “ACROSTIC REBUS” and its “SOLUTION” printed in the “POETS CORNER” of the Massachusetts Spy, on May 15 and 23, 1771 respectively, combine a paeon to Boston with an invocation of nascent revolutionary values. On the one hand, the guide to the “Sagacious reader” explains that the rebus’ “initial letters point [to] the happy place / Where num’rous charms attract the youthful lover . . . .” On the other, the actual questions posed in the poem provoke the so-called shrewd reader to consider “Who stript us of our freedom in degree? /. . . . Who spilt our blood like glorious sons of war? / Whom do the friends of Liberty abhor?”

The following week, an unidentified “L.B.” happily informs the editors: “I’ve examined the Rebus, from th’initials I find / That Boston’s the name, that the author design’d”: i.e., “BOSTON’s” the answer and “the place where many beauties dwell.” Yet, the larger “SOLUTION” printed with L. B. ‘s reply provides a more bellicose key to the puzzle’s meaning: “Our mother Britain, fain would make us slaves: / . . . / Soldiers did spill our blood, like sons of war / and Tories, friends of Liberty abhor.” In this double decoding, “Boston” functions simultaneously as a relatively innocuous place of amorous delights “[i]n form, in mind, in manners and in face,” and as the source of capital letters out of which a rhetoric of civic rebellion and exclusively white, metaphoric “emancipation” can be written. 4

How might these civic Acrostic Rebuses and their layers of encoded solutions add to our understanding of the poetic exchange that Phillis Wheatley Peters places at the end of her volume? Keeping that popular form in mind, “sagacious” readers may observe how Wheatley Peters amplifies the genre’s use of double and juxtaposed meanings to further its hidden discourse of rebellion in her own version.

In their Introduction to The Digital Black Atlantic (2021), Roopika Risam and Kelly Baker Josephs invoke W.E.B. Du Bois to explain that “juxtaposition is never mere addition but rather a transformative, alchemical move, where the sum of the parts is much greater than the whole, where analytical possibilities are opened up in the act of juxtaposition” (Josephs & Baker ix-x).

A similar productive “transformational . . . move” emerges from Wheatley Peters’ acrostic rebus placement. The rebus, founded on a principle of juxtaposition itself, in Wheatley Peters’ hands expands the realm of “analytical possibilities” to empower the doubly disenfranchised Author both to answer her interrogators from Massachusetts’s elite circles in kind and to claim a space for her own political commentary among the “citizen poets” of the emergent Boston public sphere.

On first reading, Wheatley Peters’ “Answer,” seems a straightforward celebration of Britannia’s domination of the colonies, one that unites the Exodus story of a divinely sanctioned nation wandering in the “dreary waste,” with the “tall, graceful, rampant Unicorn” on “Britain’s royal standard”–the emblem of Imperial rule. Wheatley Peters further connects the Emerald to “regal crowns,” and places Boston itself in a classical context of “beauteous nymphs” and multiple irresistible “Helen”s, followed by a scene of warring empires from Iliad XVII. As such, the “Answer” seemingly reinforces the imperial argument of the “Rebus” to which it responds.

Accordingly, the ostensible solution to the “Rebus” turns out to be “Quebec”–in I.B.’s words, “a vanquish’d town, / that adds fresh glory and renown / to old Britannia’s fame.” Likewise, Wheatley Peters appears to highlight Britain’s power in her expanded exegesis, stating,

Quebec now vanquish’d must obey,

She too must annual tribute pay

To Britain of immortal fame,

And add new glory to her name.

Read this way, the poem would have been better suited for publication ten years prior, when Britain had just gained the territories of “New France” as part of the treaty of 1763. By 1773, however, Quebec’s status as exemplary colony had dissolved into disputes over limited representation, Catholic persecution, and annual tribute now seen as exorbitant taxation. Moreover, Quebec now not only represents a continued site of British, French, and emerging pro-revolutionary hostilities, but has become a region with over 4000 enslaved Africans, primarily controlled by British elites. At this point, the obedience that Wheatley Peters claims Quebec’s “vanquish’d must” display, like the “annual tribute” they “too must . . . pay,” no longer constitutes an unquestionable right. In the 1770s spatial imaginary, Quebec as “solution” now points to the highly contested ground of Anglo-American imperial relations just months before the Quebec Act of 1774 which, with other “Intolerables,” will soon lead to revolution.

As Bassard demonstrates, in her “Answer” Wheatley Peters responds not only to I. B.’s claims of Quebec’s subjection but also to his and his fellow compatriots’ claims for her own. In its opening lines, “The Author of these POEMS” describes how, like Quebec in the face of “old Britannia,” “Phillis can’t refuse / To shew th’obedience of the Infant muse.” Yet, by the third line, “The Author” has overridden that obedience with the counter-assertion that “She knows” all possible answers to the puzzle.

By placing her rebus pair in tandem at her work’s end, Wheatley Peters confronts her interrogators not only from a distance but, in the case of I.B., face to face. The positioning plays on the convention of delayed responses that were a material feature of the rebus printed in weekly newspapers, reducing the temporal suspense of puzzling–and the indemnifying distance between rhetorical question and rebellious response–to a mere turn of the page. “Sagacious” readers, familiar with the Massachusetts Acrostic Rebuses in particular, would identify in her “Answer” the combination of idealized civic eroticism (conflating female cities with their attractive inhabitants), and colonial discourses of subjection (threatening to erupt into warfare), that characterized the regional form of the genre.

Thus, through placement and content of her poetic challenge, Wheatley Peters signals her entry into the public and overtly politicized literary realm of the POETS CORNER, in which contestants are known only by semi-anonymous initials and the seeming protections of aristocratic patronage or solitary literary composition have been removed: but where strategic juxtapositions and covert ciphers allow compensatory discourses of resistance to become legible. By 1774, those discourses would become overt and the (self-) emancipated Wheatley Peters could scrutinize openly, again in the Massachusetts Spy, “the strange Absurdity of their Conduct whose Words and Actions are so diametrically opposite,” asserting bitingly, “How well the Cry for Liberty, and the reverse Disposition for the exercise of oppressive Power over others agree,– / I humbly think it does not require the Penetration of a Philosopher to determine—” (McBride 2001 117-118).

1 We follow Honorée Fanonne Jeffers (Jeffers 2021), in using Wheatley Peters’s preferred name after her marriage in addition to the one by which she is most known.

2 This epistolary affidavit describes the interrogation of the author, referred to only by her first name, held by Massachusetts luminaries in order to “assure the World” that the book’s poems are “really the Writings of PHILLIS.” Literary scholars and historians continue to debate its historicity. For a recent account, see Kendi 2017; see also Carretta 2011, Wilcox 1999, Holloway 1995, and Henry Louis Gates, The Trials of Phillis Wheatley: America’s First Black Poet and Her Encounters With the Founding Fathers (New York: Basic Books, 2003).

3 On Wheatley Peters’ role in the editing and typographical signification of her works, see Bly 2014.

4 Kendi 2017, 107.

Bassard, Katherine Clay. Spiritual Interrogations: Culture, Gender and Community in Early African American Women’s Writing. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1999.

Bly, Antonio T. “’By her unveil’d each horrid crime appears’: Authorship, Text, and Subtext in Phillis Wheatley’s Variants Poems.” Textual Cultures, Vol. 9, No. 1 (Winter 2014), 112-141.

__________. “’On Death’s Domain Intent I Fix My Eyes’.” Early American Literature, Vol. 53, No. 2 (2018) 317-341.

Bynum, Tara. “Phillis Wheatley on Friendship.” Legacy, Vol. 31, No. 1 (2014), 42-51.

Carretta, Vincent. Phillis Wheatley: Biography of a Genius in Bondage. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011

Citizen Poets of Boston: A Collection of Forgotten Poems, 1789-1820. Ed. Paul Lewis. University Press of New England, 2016.

Holloway, Karla F.C. “The Body Politic” in Subjects and Citizens: Nation, Race, and Gender, ed. Michael Moon and Cathy N. Davidson. Duke UP, 1995

Jeffers, Honorée Fanonne. The Age of Phillis. Wesleyan University Press, 2021

Josephs, Kelly Baker and Roopika Risam. ”Introduction.” The Digital Black Atlantic ed. Josephs and Risam, ix-xxiv. University of Minnesota Press, 2021.

Kendi, Ibram X. Stamped From the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America Bold Type, 2017

McBride, Dwight A. Impossible Witnesses: Truth, Abolitionism, and Slave Testimony. NYU Press, 2001

Shields, John C. The American Aeneas: Classical Origins of the American Self. Univ Tennessee Press; (November 10, 2004)

Wilcox, Kirstin. “The Body into Print: Marketing Phillis Wheatley.” American Literature, Mar., 1999, Vol. 71, No. 1, 1-29.