Although we mostly experience rebuses on paper, and increasingly in pixels, the first rebus was printed on a clay cuneiform tablet almost 5000 years ago when an anonymous scribe substituted the image of a reed for the Sumerian homophone “reimburse.” While linguistic theorists cite this as the oldest example of the “Rebus Principle” (in which a thing is represented by a picture of another thing with the same sound), Egyptian writing systems developed autonomously around 3000 BCE, using similar combinations of visual and phonological elements. Moreover, two equally significant writing systems that also employ forms of the Rebus Principle—the Chinese and the Mesoamerican—emerged simultaneously yet independently around 1200 BCE.

Thus, a range of materials–stone, papyrus, clay, mulberry and other bark or pulped vegetable matter–provided the ground for ancient rebuses, often but not always produced in two-dimensional form. This Egyptian example represents the name of the ruler (Ramses II) as the falcon-god RA, a child MES, and a stalk of papyrus SU in a colossal granite statue that embodies his divinely royal identity three-dimensionally.

Indeed, rebuses show up on all sorts of material in all sizes from antiquity to the present: the Greeks and Romans placed them on metal coins, as tiny but far-reaching agents of empire, to indicate the name of an important town or powerful individual, but rebuses also circulated on similar materials in Georgian and Victorian Britain as more anonymous, less commanding tokens of significance: including this tag left with a foundling in 18th-century London:

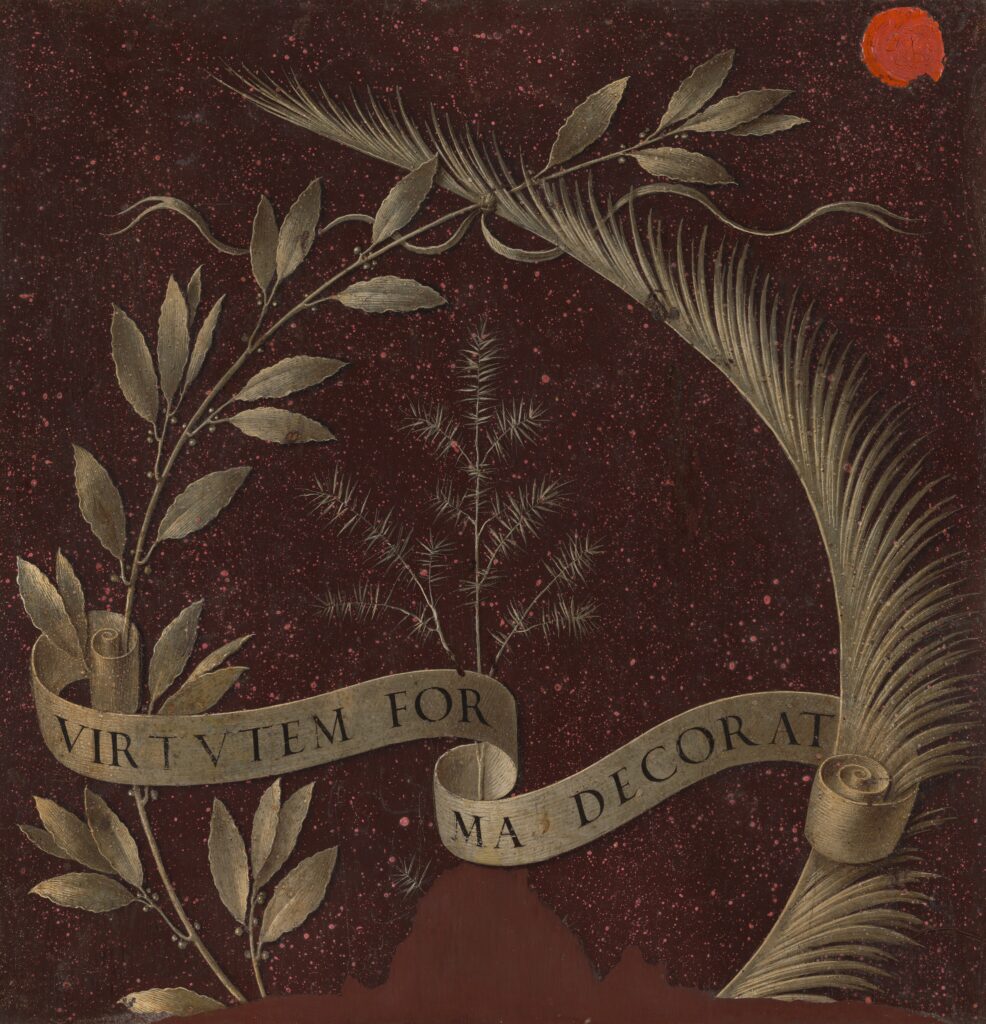

A 1585 introductory letter to Paolo Giovio’s Discourse of Rare Inventions both Military and Amorous praises all manner of ground for emblems and imprese, “whether the invention bee embroidered in garments, grauen in stone, enchased in golde, [or] wrought in Arras:” (tapestry). European early modern patrons, passionate for works all’antica, commissioned rebuses of all sorts for their personal Renaissance brands, as with Leonardo da Vinci’s c. 1578 portrait of Ginevra de Benci, which depicts the ginepro (juniper) on its obverse and reverse as a homophone for the sitter’s name.

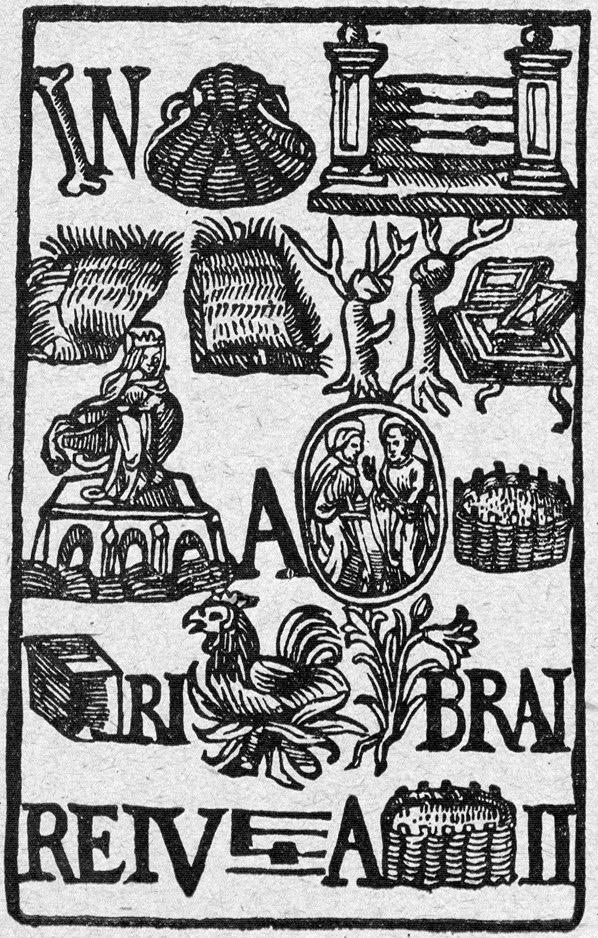

Soon, however, the artisan creators of rebuses, in paint, in bronze, or in the emerging medium of print, sought the same elevation of status conveyed by the rebus’s association of wit with individual identity. By devising puzzles from their own names, as their artist signature (D+osso [bone]=Dosso Dossi) or in a publisher’s colophon, they encouraged viewers to linger over the specifics of the work’s production and how it could be acquired in an expanding market economy.

As the custom of self-fashioning through rebuses spread outward from aristocratic circles, so did critique of such performances: in their plays, despite their own upwardly mobile ambitions, both the Venetian Pietro Aretino and the London Ben Jonson mock tradesmen and middling sorts who call attention to themselves by wearing rebuses on their clothing or commissioning them for their shop signs.

Print, in turn, allowed non-elite women more widely to display rebuses as signs of their own clever verbal literacy, as in the patterns by Stefano della Bella for embellished paper fans that invite intimate proximity in order to be solved or flaunt the bearer’s aspirations to aristocratic standards of “fairness” or whiteness coupled with pithy mottoes on Fortune or Love.

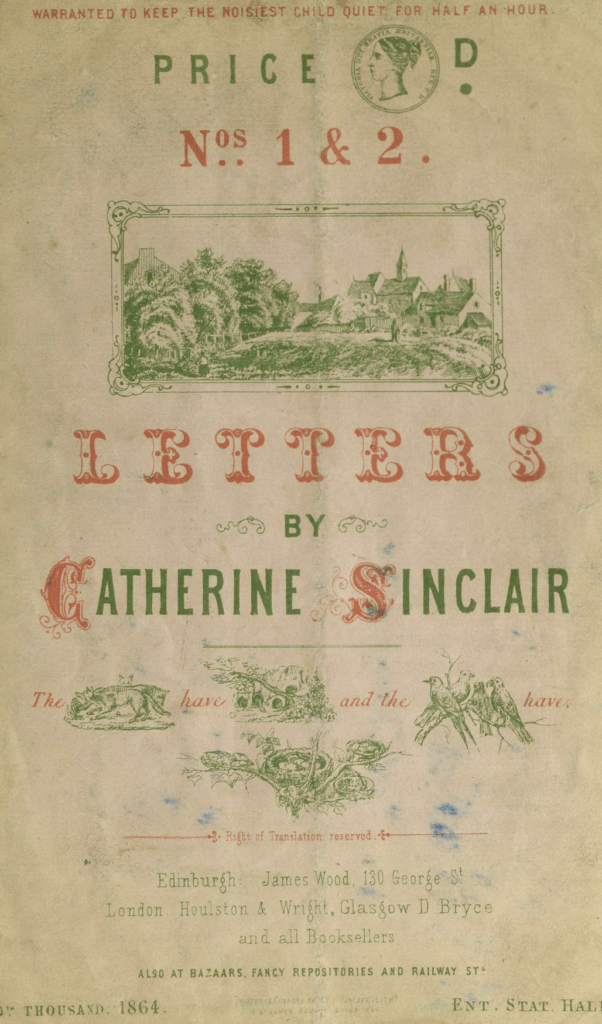

At the same time, the expansion of print and female literacy in the 18th and 19th centuries increasingly gave rise to women not just consuming but producing rebus ephemera and collections for profit. Both printer Mary Darly’s satirical caricature and rebus combinations designed and sold at her shop in London and the Scottish novelist Catherine Sinclair’s rebus puzzle books aimed at molding proper juvenile behavior through the guise of entertainment recognized emergent transnational markets for the rebus’s potent combination of instruction and delight.

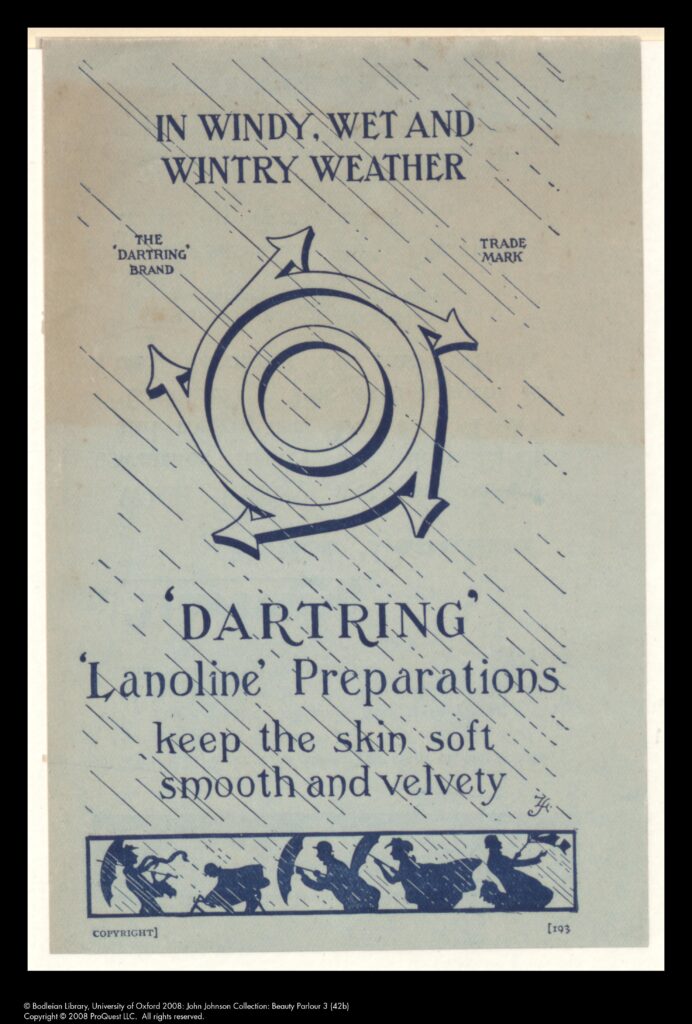

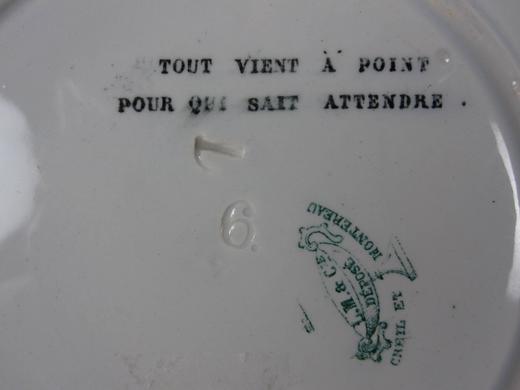

As rebuses circulated ever more broadly in cheap and brittle media, they were expected less to last as material objects than to advertise how one might acquire new commercial goods produced through global trade and industrialization–flour, tobacco, shoes, skin cream. Nonetheless, these visual puzzles occupied increasing space in middle-status homes, fashioning the Western liberal subject through regular appearances as popular entertainment in weekly periodicals, but also on sewn samplers, in children’s Bibles, even dinner plates and tea services.

In his 1964 book, Rébus, Max Favalelli recalls from his youth, “bowls on which were reproduced those nice [gentils] rebuses and which were for my parents a precious addition, as I rushed, without the slightest urging, to eat my soup every night until discovering with delight under the vermicelli or the tapioca the puzzle that over and over again had already been solved”; to which the critic Jean-François Lyotard adds, dryly, of this primal dinner scene, “I leave the reader to judge [the situation]: the soup thrust by the parents between the child and the enigma, the repetition of the discovery . . . .” Here the resistant yet “meaningless” materiality of the meal must be consumed (durum wheat or manioc, the child is indifferent), before the material substitutions of the rebus can be conquered and enjoyed. But, as Favalelli might have learned from decoding his (now empty) bowl, “Good things come to those who wait.”

Bolzoni, Lina. The Gallery of Memory : Literary and Iconographic Models in the Age of the Printing Press. University of Toronto Press, Scholarly Publishing Division, 2001.

Céard, Jean and Jean-Claude Margolin. Rébus de la Renaissance: des images qui parlent. Paris, Maisonneuve et Larose, 1986.

Dosso’s Fate: Painting and Court Culture in Renaissance Italy, ed. Luisa Ciammitti, Steven F. Ostrow, and Salvatore Settis. Getty Research Institute, 1998.

Giovio, Paolo. The Worthy Tract of Paulus Iouius, . . . trans. Samuel Daniels. London, Simon Waterton, 1585.

Lyotard, Jean-François. Discours, figure. Paris, Klincksieck, 1974.

Rauser, Amelia. “Hair, Authenticity, and the Self-Made Macaroni” Eighteenth-Century Studies, Fall, 2004, Vol. 38, No. 1, pp 101-117.

Ricouart, Pierre. http://www.bvh.univ-tours.fr/batyr/beta/notice_bois.php?IdBois=28363

Visible Language: Inventions of Writing in the Ancient Middle East and Beyond. Ed. Christopher Woods, Emily Teeter, Geoff Emberling. Exhibition Catalogue, University of Chicago, 2010.

Very interesting article.