Coats of arms and other forms of heraldry occupy a curious position in the realm of rebuses. At a glance, not all instances of heraldry are rebuses: for instance, a coat of arms with iconography consisting mostly of lines and shapes is far less likely to have the potential to be a rebus than, for instance, a coat of arms featuring a motto and highly-detailed supporters (that is, the animals or other entities on either side of the coat of arms). This ambiguity stems not only from the fact that even more than other rebuses, coats of arms blur the line between artistic composition and puzzle, although often with an amount of bias towards artistic composition, but also because “reading” a coat of arms requires a somewhat different mindset than “reading” a rebus.

With a coat of arms, one must consider a number of aspects of not only its composition but also its context, in a manner that may resemble gathering clues or performing an investigation more than solving a puzzle. To elaborate, “solving” a coat of arms requires making connections and inferences in the same vein as a rebus might, but often in a different manner and potentially for a different purpose: establishing or discovering more about context. Consider a coat of arms that one knows is for a family with the surname “Bearington,” with a composition consisting of two bears as supporters and an orchard as the compartment. On a more explicit level is the connection between “Bearington” and “bear,” while the connection between “Bearington” and the orchard is a little more obscure, with “ton” being part of the word “Appleton” (referring either to the town or the toponym: the apple orchard could allude to either).

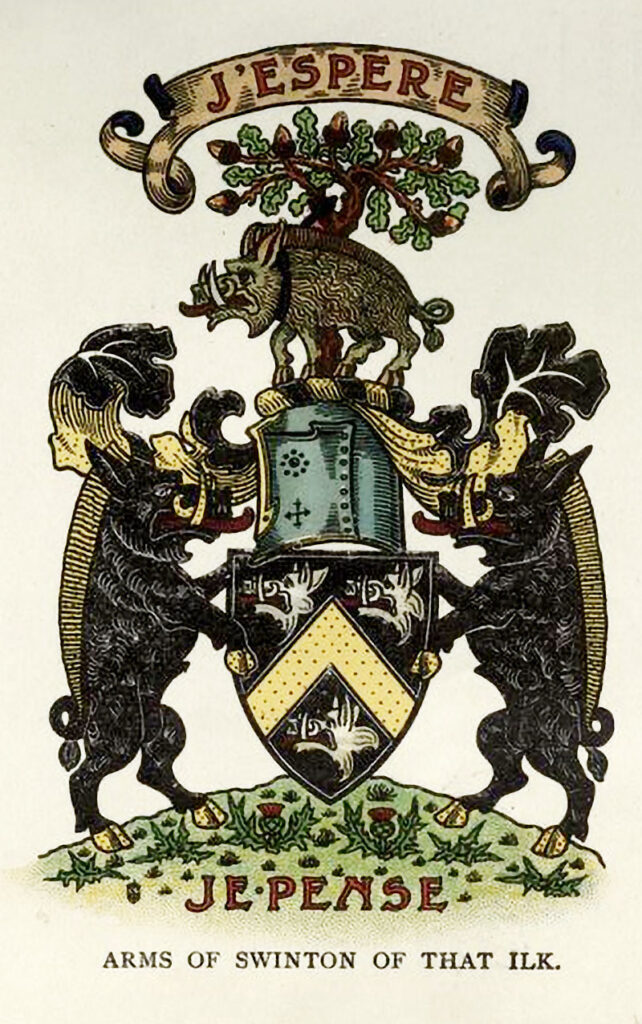

Coats of arms also have a much higher degree of ambiguity than other rebuses, not only due to the reliance on inferences and the experience and background knowledge of rebuses one needs in order to engage with them in this way, but also due to cultural context. The theoretical “Bearington” family arms could function as heraldry for a family with the surname “Verdier-Ouvrard” (although a bit less directly): “verger” is French for orchard, and “ours” is French for bear. When one takes into account the differences in symbolism between cultures, it also becomes clear that a coat of arms in one culture could have a completely different meaning elsewhere – for example, the boar that fittingly appears on the Lowland Scottish Clan Swinton’s coat of arms (boar are swine, “Swinton” resembles “swine”) might carry an implication of impurity or filth in, say, a Hebrew society.

Notably, coats of arms don’t feature the same sort of anti-Barthesian aspect as prominently as other rebuses, partially because rebuses play more of a specifically emergent role in heraldry. Rather, when examining a coat of arms like a rebus, the creator’s intent may need to be shunted to the side.